Potential influence of sulphur bacteria on Palaeoproterozoic phosphogenesis

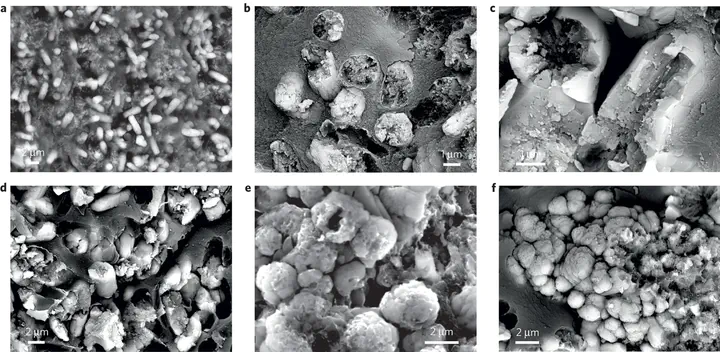

SEM–BSE images of cracked rock surfaces illustrating apatite particles (BSE light) and the massive carbonaceous matrix (BSE dark) in phosphate nodules and layers.

SEM–BSE images of cracked rock surfaces illustrating apatite particles (BSE light) and the massive carbonaceous matrix (BSE dark) in phosphate nodules and layers.

Abstract

All known forms of life require phosphorus, and biological processes strongly influence the global phosphorus cycle1. Although the record of life on Earth extends back to 3.8,billion years ago2 and the advent of biological phosphate processing can be tracked to at least 3.5,billion years ago3, the earliest known P-rich deposits appeared only 2,billion years ago4,5. The onset of P deposition has been attributed to the rise of atmospheric oxygen 2.4–2.3,billion years ago and the related profound biogeochemical shifts6,7,8,9, which increased the riverine input of phosphate to the ocean and boosted biological productivity and phosphogenesis5,10. However, the P-rich deposits post-date the rise of oxygen by about 300,million years. Here we use microfabric, trace element and carbon isotope analyses to assess the environmental setting and redox conditions of the 2-billion-year-old P-rich deposits of the vent- or seep-influenced Zaonega Formation, northwest Russia. We identify phosphatized microorganism fossils that resemble modern methanotrophic archaea and sulphur-oxidizing bacteria, analogous to organisms found in modern seep settings and upwelling zones with a sharp redoxcline11,12. We therefore propose that the P-rich deposits in the Zaonega Formation were formed by phosphogenesis mediated by sulphur bacteria, similar to modern sites13, and by the precipitation of calcium phosphate minerals on microbial templates during early diagenesis.