Palaeoproterozoic oxygenated oceans following the Lomagundi–Jatuli Event

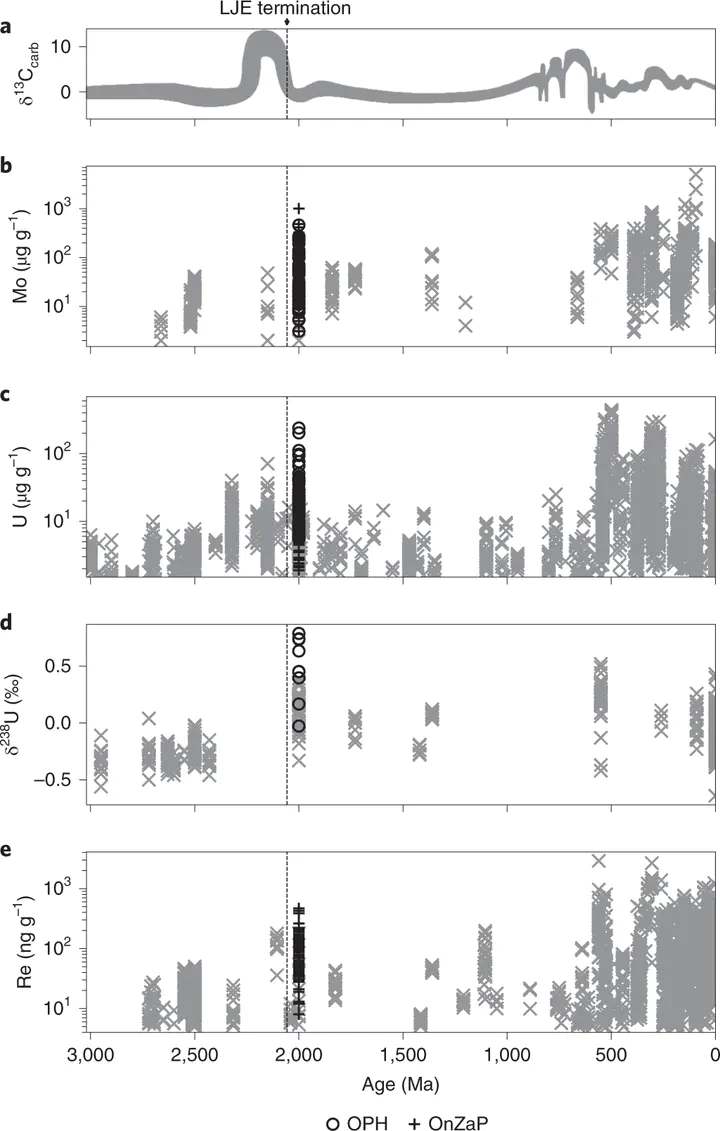

Secular trends in RSE concentrations from anoxic shales. Zaonega Formation data (plus and circle symbols) are plotted on compilations from the literature (× symbols). a, Changes in δ13Ccarb through time. b, Mo concentrations. c, U concentrations. d, U isotope ratios. e, Re concentrations.

Secular trends in RSE concentrations from anoxic shales. Zaonega Formation data (plus and circle symbols) are plotted on compilations from the literature (× symbols). a, Changes in δ13Ccarb through time. b, Mo concentrations. c, U concentrations. d, U isotope ratios. e, Re concentrations.

Abstract

The approximately 2,220–2,060 million years old Lomagundi–Jatuli Event was the longest positive carbon isotope excursion in Earth history and is traditionally interpreted to reflect an increased organic carbon burial and a transient rise in atmospheric O2. However, it is widely held that O2 levels collapsed for more than a billion years after this. Here we show that black shales postdating the Lomagundi–Jatuli Event from the approximately 2,000 million years old Zaonega Formation contain the highest redox-sensitive trace metal concentrations reported in sediments deposited before the Neoproterozoic (maximum concentrations of Mo = 1,009 μg g−1, U = 238 μg g−1 and Re = 516 ng g−1). This unit also contains the most positive Precambrian shale U isotope values measured to date (maximum 238U/235U ratio of 0.79‰), which provides novel evidence that there was a transition to modern-like biogeochemical cycling during the Palaeoproterozoic. Although these records do not preclude a return to anoxia during the Palaeoproterozoic, they uniquely suggest that the oceans remained well-oxygenated millions of years after the termination of the Lomagundi–Jatuli Event.